M. Night Shyamalan is young at heart and wise beyond his years. That’s the take away I keep coming back to after seeing his new film Old for the second time in theaters.

I came to film slowly, but with increasing intensity. A major part of that was when I visited my cousins who lived in suburban Pennsylvania. I watched Toy Story 2, The Matrix, James Cameron’s Avatar and the Star Wars Prequels in on DVD in their basements between moving cities and countries. I remember one summer they wanted to show me a local hero of theirs; M Night Shyamalan.

That was around 2005-2007. My cousins were obsessed with arguably his three best movies, The Sixth Sense, Unbreakable, and Signs, undoubtedly because my uncle worked in Philly, and Signs was filmed in their Bucks County. They had made sure not to show me his more recent works, and had yet to see his much maligned adaptation of their beloved Last Airbender.

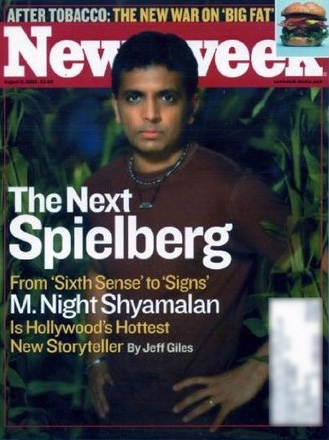

Shyamalan had just gotten off a rollercoaster. He had gone from making a few little known films, to selling The Sixth Sense on spec for a reported 3 million dollars. The Sixth Sense was a phenomenon, and three years later, a famous Newsweek cover declared him the next Spielberg.

Shyamalan soon crashed. His name became a punchline almost as quickly as it became synonymous with storytelling. Amongst many, his name is still a joke. But M. Night kept working.

Starting with 2015’s The Visit, Shyamalan began working on smaller projects by self financing his movies. The Visit and Split were both made for under $10 million, and Glass was made for less than $20 million. All were big hits, with The Visit making $98 million worldwide, and Split and Glass making over $200 million worldwide. Self financing allowed Shyamalan to have smaller budgets, let him take bigger creative risks. He has said that those risks gave him the personal pressure to be creative again, to go back to that feeling when he was in his 20’s, trying to sell The Sixth Sense to studios.

Observing from the outside, Old seems to be a culmination of those experiences. His latest film oozes with confidence that he can make a more ambitious film and have it pay off. That confidence is something that doesn’t break into the mainstream enough. It’s something reserved for filmmakers who are confident in their craft, and who have something to say.

Spoilers below…

Old has an all star cast led by Vicky Krieps andGael Garcia Bernal. They play the parents of a family going on a tropical vacation. From the first moments of the film, Shyamalan is introducing the audience to the characters in the simplest way. We get the dynamic of the family instantly and soon learn of their trip to this remote resort. They go to the beach and the daughter Maddox (played by Alexa Swinton and later Thomasin McKenzie) instantly looks at a group of teenagers playing volleyball. Without words, Shyamalan has introduced the irony that this character wants to be older.

Old is filled with visual storytelling like this. He uses the camera and the grammar of cinema to communicate visual story ideas. The frame cuts off the heads and feat of the characters to indicate the characters’ disorientation and claustrophobia when they’re on the old beach. Well timed cuts to the pounding waves show how the characters can’t escape the beach, and imply the harsh impact of death. Minnows pick at the son Trent’s (Played by Nolan River, Luca Faustino Rodrigues and Alex Wolff) feet as he’s in the resort beach, disappear when he’s at the lifeless old beach, and reappear when he and Maddox finally escape. When the parents finally die of old age, the camera swings back and forth up the shore, implying the inevitability and serenity of death.

This is sophisticated visual storytelling, worthy of Shyamalan’s well known inspirations Spielberg and Hitchcock. In these moments it’s more concerned with communicating these complex ideas in the most sophisticated way possible. It’s an art house film. But it isn’t merely that. It is also a schlocky American horror movie, reminiscent of B movies of the ‘50s like Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or The Creature From the Black Lagoon, of the expositional parts of Psycho, and of The Twilight Zone.

These works are concerned with exciting the audience with strange ideas that excite, and get to a wide audience. They have moments of visual creativity, but they also deal with heavy handed metaphors that cannot be called subtle.

Old is not subtle. It’s about all of these people living their entire lives on the beach. Their entire lives. It crams all of the emotions and plot points, into a day. Those of death, loss, hatred, disease, divorce. Those of love, birth and forgiveness. Shyamalan uses big performances and stilted dialogue to communicate these plot points and these emotions in under two hours. It’s clunky, it’s unsubtle, it’s not completely logical.

Characters espouse exposition constantly to move the plot along. That has turned many, many audience members and critics off. Yet for me, it speaks to both the schlocky horror films that Shyamalan draws inspiration from, and the inherent discombobulation of seeing all of life pass before your eyes in such a short period of time.

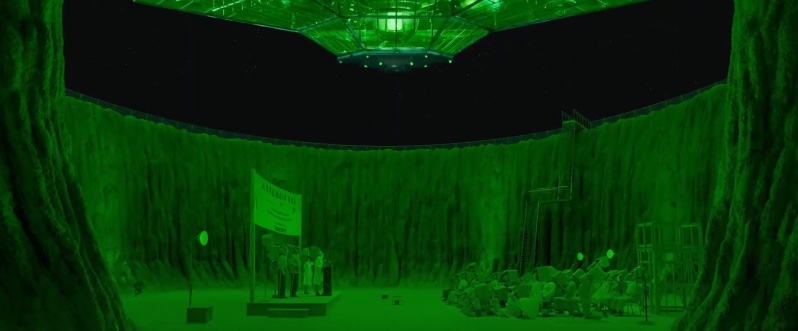

This also comes into play with the twist ending of Old. He could have been ambiguous with his ending, keeping the nature of the again process unsaid and leaving us with the unsettling nature of our own mortality. But he’s also giving us that Twilight Zone explanation. The hotel is run by a drug company that’s using the beach to test drugs in a day instead of in a lifetime. This wraps up things neatly, but it also follows the logical extension of the premise. If there was a beach that made you old, giant corporations would probably try to exploit it for profit.

Shyamalan is pulling from both of these traditions simultaneously. He’s using his premise of a beach that makes you old to meditate on family, aging, and the fragility of our bodies using visual metaphors. He’s also pulling from genre tradition that explains things to a wide audience. Both nationally and internationally. Simple and a simple premise dialogue allows him to reach a large audience. Complex visual storytelling allows him to to go deep with that premise.

I think a lot of critics of Old are missing the tension that he’s playing with here. Old is stilted. It’s unsubtle. It’s inelegant in lots of places. But that doesn’t take away the simplicity of the premise. The premise that you live a lifetime in a day has so much juice that he’s able to play with it endlessly. It’s youthful. He’s having fun with the body horror of the premise, and he’s taking risks that no grizzled studio veteran would allow him to do.

Yet at the same time he’s injected lots of wisdom into the film. Bernal and Krieps argue in the beginning of the film, and are about to get divorced, but by the end they learn to forgive each other. The family that learned to survive was the one that stuck together and forgave each other.

The wisdom is also shown in Shyamalan’s filmmaking process. After a tumultuous decade, he’s learned his limits. He speaks of his inability to handle big budget films, and that he’s at his best when he’s working with small budgets. He’s created an environment where he can work with collaborators who trust in him. (Including his daughters.) Where he can experiment with smaller projects with bigger ambitions, rather than with the blank checks a Spielberg or a Cameron gets.

All of this is shown in one of the final scenes in Old. When Trent and and Maddox have spent an entire day on the beach, now in their 50’s they decide that they shouldn’t give up on escaping the beach. They should try and get off the beach, but they should build a sandcastle first. They’ve learned that you must enjoy live in the limited time you have. To use the wisdom of your life experiences while still being able to look at things fro a child’s eyes.

Old is many things at once. It’s clunky and elegant. It’s subtle and in your face. It’s simple and complex. Not everyone will like it. That’s because it’s an M. Night Shyamalan film through and through. It’s incredibly personal. It feels wrong for Shyamalan not to swing for the fences. He’s kept in touch with what made him connect with me and my cousins in a basement Bucks County. I love him for that. And I love Old for that. People should go check it out.

Old is in theaters now.