Wes Anderson’s 11th feature film is a repetition of everything else Anderson has done before. He uses much of the same acting company, the same cinematographer, and one of the same co-writers as his prior projects. This repetition has split those who watch his work between those who dismiss him as nothing deep, all aesthetic without substance, and those like me who’ve gotten on the proverbial train and don’t plan to get off.

But for me, this repetition represents a refinement of the themes the writer-director has been exploring since he tried to make Bottle Rocket in 1994. That year, Anderson, Owen and Luke Wilson and their small crew tried to make their feature screenplay with money from their fathers. When they failed and ran out of money, they took their footage and submitted it as a short to Sundance. His themes and style have been there for 29 years. For me, Anderson has always been the same guy, telling stories about broken and sad people, hiding behind a facade of civility. What’s changed is his genres and mediums, all while he’s advanced in his technical prowess, and his willingness to lead the audience into deeper and deeper themes.

Asteroid City is no exception. Spoilers below.

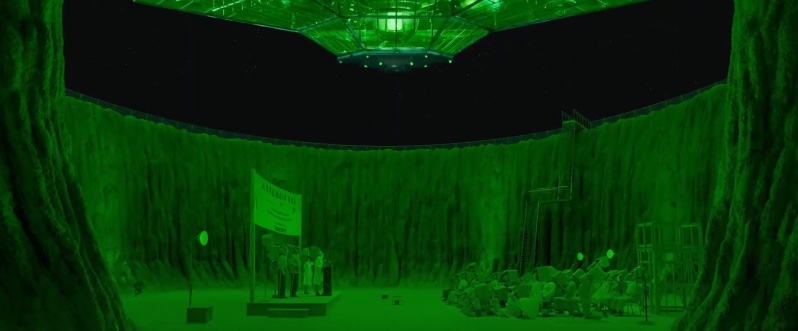

Asteroid City opens jarringly with a message from a TV presenter played by Brian Cranston. The movie we are watching is in fact a television program which recreates a play that was written by a Southwestern playwright portrayed by Edward Norton. All of the characters we know from the trailers and the posters are presented as actors, who are to play the characters in a theatrical performance on the stage. The film then goes from a crisp black and white in academy ratio to a vibrant technicolor in scope. The theater performers, through the art of acting, are presenting the story in a vibrancy that mimics the emotions of the cinematic.

The credits roll as we watch a train roll through the American desert. The locomotive carries nuts, fruit, passengers, automobiles, and nuclear weapons. There is a deep darkness lying alongside the pristine desert that is bathed in “clean light.”

We then meet Augie Steenbeck, a war photographer played by Jason Schwartzman who needs to take his four children to stay with their Grandfather, played by Tom Hanks. But Steenbeck hasn’t been able to tell his children the awful truth that their mother has been dead for three weeks, and that they are on their way to bury her. The family’s car breaks down in a land scarred with craters from nuclear bombs and a crater from a meteorite that landed 5,000 years ago.

Steenbeck is an atheist, and is unaware of how to tell his children that their mother has left them. That entered the unknown beyond this mortal coil. He isn’t Episcopalian like his father in law or his children, so he has no honest answers for them. All he knows is that the passing of his wife into that dark unknown has left him scarred, and he doesn’t know what to do.

Steenbeck’s son Woodrow, played by Jake Ryan, is interested in the unknown. He is a junior stargazer who’s won a science competition where he and other stargazers present inventions to the scientific community and the US military while gazing at an astronomical anomaly inside the crater.

There are a lot of important characters and subplots that intersect Augie and Woodrow’s journey as they process the loss of their wife and mother. Stanley Zack (Hanks) challenges Augie about how he’s running away from telling his children about their mother’s death. When Augie says he couldn’t find the right time to tell them, Stanley says the moment is always wrong. Midge Campbell (Scarlet Johansson) is a movie star preparing for a roll, running from her past relationships and taking her daughter to the stargazing event. She challenges the way Augie takes pictures with no regard to other’s feelings, how he uses his precise photography to control the chaos of the wars of the world, and the grief swirling inside of him.

Midge’s daughter flirts with “brainiac” Woodrow, while she and the other cadets challenge him to come out of his shy shell. Dr. Hickenlooper (Tilda Swinton) challenges Woodrow to keep exploring the vast unknown of space, despite the attempts of the government and military to control the town, the cadet’s inventions, and the unknown itself.

But to me, the real heart of the story comes when the group is visited by an alien being at the stroke of midnight. The alien steals the meteorite and leaves, posing endless questions for the characters and the audience. Why is it here? What did it want? What will it do? Is there a meaning to the universe? To life? Is there a point? Does the alien have answers?

These are classic questions raised by countless characters in the annals of American science fiction, and must be raised by any entry in the genre. In Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Spielberg’s protagonist nearly goes mad trying to find the answers, pushing his family away in the process. But this is where Anderson diverts from most other sci-fi. By using his same old techniques, his same old repetition that he is so often decried for, Anderson reaches a profundity that few other entrants in the genre are able to achieve.

Throughout the telling of the story of Asteroid City, from fourth wall breaks, to set design, to act breaks, we are reminded that this is a theatrical performance. Brian Cranston told us at the beginning of the movie, and throughout the rest of the movie, he tells us some context on how that play was made.

Edward Norton plays Conrad Earp. A renowned playwright. He wanted to tell a story that would transform people’s lives, that would transform the actor’s as they were performing it. We also learn that Earp had an affair with the actor who plays Augie Steenbeck, and that Earp was inspired by that actor and wrote the part of Steenbeck around him.

But right before production, Conrad Earp dies, leaving the director and the rest of the cast with no guidance. There are no answers from the play’s creator. The actor playing Steenbeck is distraught. We cut between the actor in the play, and the character of Steenbeck. Both looking for answers about the point of it all. The meaning of what they are doing here. If they are helping his children grow up properly, if they are helping the audience understand the intent properly. But they are given no answers. They are only left with the crater of their grief. Surrounded by other people trying to figure out what’s going on in this chaotic world. Trying to keep themselves from falling into the abyss of madness while what we knew unravels before us.

In this moment, the actor playing Steenbeck stops the play, runs across the backstage and asks the director (Adrien Brody) if he’s doing it right. He confesses that he doesn’t know his motivation, the intent of the author, and he wants to know if he’s messing it up. The director tells him that he’s doing it right. He doesn’t need to understand everything, he just needs to keep playing the part, and the rest will follow.

“All the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players.”

We don’t have all the answers. Atheists and Episcopalians alike can’t grasp the vastness of the universe, or the emptiness of our own hearts. The playwrite might have thought of everything, but they’re not able to tell us how to act in our own play. We must keep acting, and the act of acting in our own play will help us connect with the audience even if we can’t fully grasp the unknown. We must keep acting, and the act of acting will help us guide our children through their grief. It will help guide us through our own.

We are good enough. Even if we don’t have all the answers. And that’s the point.

Asteroid City opens in New York and Los Angeles on June 16th. It expands wide on June 23rd.