Wes Anderson has been one of the most singular figures in twenty first century cinema. His visual style is instantly recognizable, but hardly ever imitated outside of the wardrobes, interior decor, and instagram feeds of his admirers. He has been so outside the mainstream of Hollywood’s visual grammar that he’s been often maligned by those detractors who claim his work lacks any depth.

There is perhaps no better example of this dichotomy than in his latest work, The French Dispatch (Of The Liberty Kansas Evening Sun). An anthology, the film goes so much further into Anderson’s idiosyncrasies that it can appear that he’s no longer interested in delivering a satisfying narrative. However his storytelling instincts are as strong as ever. He’s merely achieved more control and sophistication over his craft as a director, and is diving into one of his longtime influences, The New Yorker to tell a story in a way no one else could.

The French Dispatch translates the final issue of the fictional magazine of the same name. It simultaneously tells the story of the written word and it’s supplemental materials, and of the process of writing it. In so doing it is an ode to journalism; not that of All The President’s Men or The Post, which expose the evils of our corrupt systems and seek to bring light to the public for accountability, but those of culture and human interest. The film’s preoccupation, and the preoccupation of the fictional writers, is that of people. How we live together, how we express ourselves and how we understand our place in the society we’ve chosen, or have been born into.

This cultural exploration is incredibly sophisticated. It uses cutaway drawings, non linear storytelling, photographs, plays, animated comic books, black and white cinematography, color cinematography, changing aspect ratios, soundtracks, TV interviews, the score, anything and everything that it can to convey what the written word can do visually. Yet the stories it tells are mostly comedic. While all of Anderson’s movies are comedies, the anthology structure of the film makes it appear to lack depth on a casual viewing. Because of this many are dismissing this as a lesser work of Anderson, which I must argue is a fatal mistake.

Spoilers below.

The first story, The Cycling Reporter is Owen Wilson’s character Herbsaint Sazerac moving though the fictional city of Ennui. He recounts the different neighborhoods and the people, animals and smells that populate its streets with a familiarity that in my experience can only be known through walking or biking through a city. In addition to speaking of Ennui’s people, it speaks to the changing nature of cities. There are things that stay the same, like the names of neighborhoods or the nature of choirboys disturbing passerby’s after mass, but things like population, shopping centers and the automobile naturally lead to change; for better and for worse.

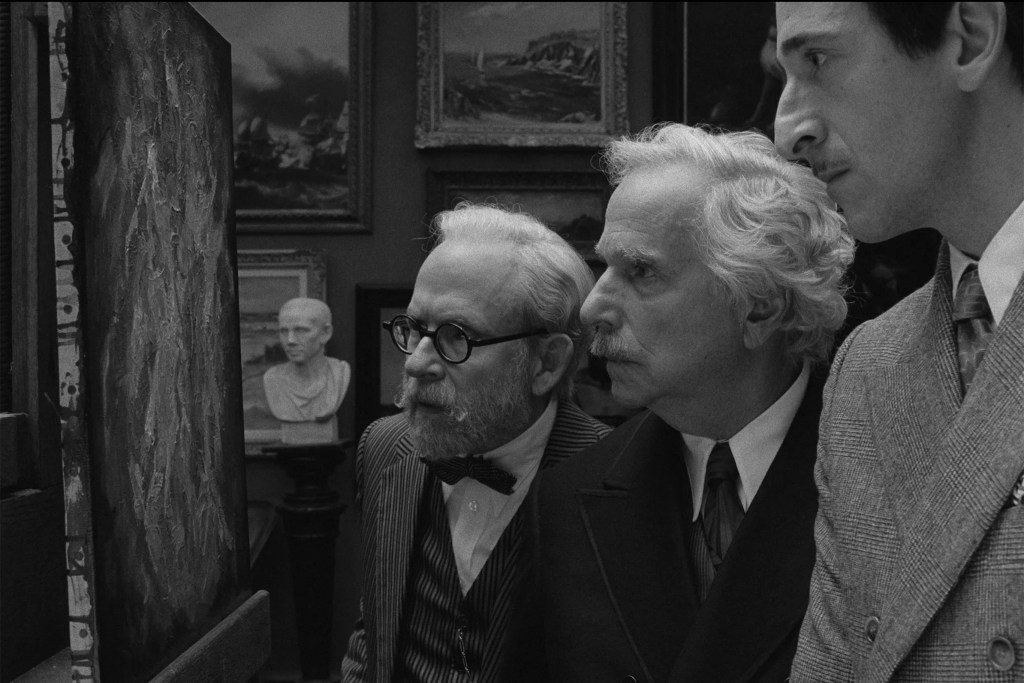

The second story The Concrete Masterpiece, follows Tilda Swinton’s character J.K.L. Berensen as she recounts the story of one of the 20th century’s most influential, fictional modern artists, Moses Rosenthaler, played by Tony Revolori and Benecio Del Toro. Rosenthaler is mentally disturbed, and is in Ennui’s insane asylum for murdering two bartenders. He is consistently on the verge of suicide, but what keeps him from ending his life is the process of making art, and his love for his muse and lover, his guard, Simone, Léa Seydoux. Adrien Brody, an art dealer imprisoned for tax evasion, is determined to make Rosenthaler famous, and to profit off of it.

The story spirals into the obsession over Rosenthaler’s masterwork “Simone, Naked, Cell Block-J Hobby Room”, and the anticipation of his follow up. Brodie and his uncles, portrayed by Bob Balaban and Henry Winkler are on a quest to manufacture Rosenthaler’s importance in order to profit from it, yet Rosenthaler’s artistic ambitions become too big for them to easily commoditize. The Concrete Masterpiece becomes about how counter cultural movements change the world, and the lengths to which capitalism will go to profit from it; as well as how the act of creation, and those they love keep the artist from losing themselves. It’s about the ecosystem of the artistic process.

The third story, Revisions to a Manifesto, follows Francis McDorman’s character Lucinda Krementz as she follows the student uprising by Timothée Chalamet’s Zeffirelli, and Lynda Khoudri’s Juliette. In it, Krementz is to interview Zeffirelli as he attempts to write a manifesto that will inspire his generation, while telling their parent’s generation what ails them.

Krementz offers to proofread Zeffirelli’s manifesto, which includes background of the movement, the pent up frustration, narcissism and tragedy of the youth culture that is unable to gain any traction in the institutions it rails against. Yet the youth movement is also disjointed, fractured, and unfocused. The student movement started out as an attempt for boys to enter the girl’s dormitory for access to consensual relations, but has spiraled into protests against imperialism, capitalism, and the mere notion that parents know more than their children. Because of this and the infighting that naturally ensues, the revolution sputters out.

Krementz become too involved with the story. She has sexual relations with Zeffirelli, and her revisions to his manifesto become so involved that they in someways sacrifice the spirit of the revolution he symbolizes. She is constantly critiqued by Juliette and other students for sacrificing her journalistic neutrality, and some claim that neutrality never existed. In this way Anderson is commenting on how journalists aren’t truly neutral actors. They have a stake in our society and how we move forward.

Furthermore he comments on how the young need mentors to learn from the mistake of the past, and to sharpen their own ideas to improve them. Again Anderson is making the case for cultural criticism and intellectual rigor by showing how even passion for cultural critiques can lead one astray without guidance.

The third story, The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner, opens with writer Roebuck Wright, played by the magnificent Jeffery Wright, recounting one of his articles for The French Dispatch to a TV personality played by Liev Schreiber. In in piece, Wright was supposed to go to a dinner cooked by Lieutenant Nescaffier, played by Steven Park, hosted by Matthieu Amalric’s The Commissaire. The dinner is about to start, when the Commissaire’s young son is kidnapped by a gang of criminals and showgirls. Wright is now to see “police cooking” a nutritious cuisine for lawmen on the fly and on the job, in action.

This final story is on its surface the most adventurous. There’s gunplay, adventure and action in Anderson’s signature style, including an animated sequence hand drawn in Angoulême, France, the same place they shot the live action sequence in the movie. But underneath that surface is some of the most heartbreaking and deep characters in all of Anderson’s filmography.

The Commissaire was once an officer of the Law in one of Frances colonies, most likely Southeast Asia. His wife died shortly after his son Gigi, played by Winsen Ait Hellal, was born. They returned to Ennui shortly after, and bonded over their shared love of police work. It is this bond with his son that drives The Commissaire so passionately, and it is why the sequence has such emotional investment.

Wright’s character is mostly based on the writer James Baldwin, who spent many years in France to escape the toxicity of America’s racism and homophobia of the 50’s and 60’s. Roebuck is also a homosexual black writer, wandering from place to place looking for purpose and connection. He is able to find it despite persecution, because of the kindness of Arthur Howitzer Jr., played by Bill Murray. Howitzer offers him a job, and more importantly purpose in writing, rigorous criticism that keeps Wright on his toes for decades on.

When the adventure is over, Wright speaks to Nescaffier. Nescaffier put himself in danger because he is an immigrant, and he didn’t want to alienate himself from the rest of his community of officers. Yet despite the danger he found purpose in his cooking, a new flavor. Wright similarly admits that he is also an immigrant, and that he has been drawn to food writing because as a wanderer, he is profoundly lonely, yet a meal with a drink and a fire is a constant source of comfort no matter what street corner he wanders down.

This observation is one of the most profound in the entire film, and to me the one that hits most personally. That for those of us who wander, it is culture, be it food, film or writing, that keeps us going in our loneliness. That the act of creating something for others will never be in vein. There will always be another lonely soul who needed you to pour your heart into what you created. Someone who needed a good meal.

The French Dispatch is bookended by an obituary for Arthur Howitzer Jr. Both the obituary itself, and the moment when his writers and staff realize his death, and begin writing it. Howitzer was born to a newspaperman in Liberty Kansas, and wanted to try a crack at managing a magazine while on vacation in France. He never left till his passing. He spent decades finding and cultivating writers, trying to push them to their best, paying them well, and bringing their work back to his hometown.

By bookending Howitzer’s story, he makes a statement on the value of culture. Howitzer brought these stories of art, youth and food to us. He placed a value in them, and presented them with tact, and craft. He showed us why we should value art and writing by presenting it in such an artful way. Like in The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson is making an argument for his aesthetic, his influences and his attention to detail. Culture is important, it helps us understand each other and ourselves, and it helps us get through difficult times. This is what Wes Anderson has done for twenty five years, and it’s what The New Yorker has done for 96 years.

The French Dispatch is like eating a meal made by an old friend. It’s warm, comforting, comes in multiple courses, and it’s familiar. You knew what you were getting when you went into his kitchen. That’s why you entered in the first place. But when you take a closer look at the meal, and when you take a peak into the kitchen to see the lengths this old friend went to to prepare this meal, it should rightly knock your socks off.

It is a film that has impeccable craft, and unexpected depth, while being incredibly entertaining and funny. I truly think it is one of Wes Anderson’s best works. It wold be a mistake to dismiss it, or to miss it while it’s in theaters.